The sub-genre that set the stage for

50 shades.

In May of 2011, an unknown British author called E. L. James used an Australian website to self-publish an erotic romance novel. The book quickly became a word-of-mouth phenomenon. In March of 2012, it was picked up by Vintage, who re-released it in a revised edition.

Fifty Shades of Grey became the fastest-selling book in the history of Penguin Random House (of which Vintage is an imprint), and the biggest-selling book of the decade in any genre. Salman Rushdie—whose novel Midnight’s Children was voted the best Booker Prize winner of all time—said of Fifty Shades of Grey that he’d “never read anything so badly written that got published.” Whether or not you agree with Rushdie, his verdict is representative of the general intellectual contempt that greeted James’s debut, which was in proportion to the novel’s commercial success.

If you’ve heard of only one work of romance or erotica, it’s probably that one. Notably, the book’s reception illustrates society’s ambivalent relationship to romance writing as a whole. It has long been one of the most popular and lucrative genres in US publishing. But romance is also the most critically neglected, both in terms of how it’s covered in the quality press and how seldom it’s studied in institutions of higher learning.

It’s a shame that romance literature is culturally stigmatized. Because exploring the genre, both as a reader and as a writer, can help you tap into your desires and have better sex.

What exactly is romance writing?

If you’re new to romance, it can be useful to know what to expect from it. The Romance Writers of America (RWA) is the industry’s largest professional organization, and it provides an unambiguous definition of the genre. “Two basic elements comprise every romance novel,” the RWA’s website states, “a central love story and an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending.” The same page defines erotica as a sub-genre of romance “in which strong, often explicit, sexual interaction is an inherent part of the love story.”

On first reading, these definitions seem restrictively precise. But there is room for apparently endless variation within the parameters they describe. The Book Industry Subject and Category (BISAC) Subject Headings List—a standard index in the publishing industry—includes 49 subcategories of romance fiction, including Historical / Gilded Age (FIC027460), Clean & Wholesome (FIC027270), and Paranormal / Shifters (FIC027310).

This formal classification only hints at the true diversity of subject matter and characterization within the genre. One of the strangest and most exciting aspects of getting into romance and erotica is the swift realization that no matter how wholesome or perverse your tastes are, someone has almost certainly already written a full-length novel—and very possibly an entire series—based on your specific turn-on(s).

Where to read (and write) romance and erotica

A good starting point is to browse the catalogs of established publishers. Some, like the romance behemoth Harlequin, offer a wide range of general titles. Other publishers focus on books geared toward specific demographics or interests, such as Bold Strokes Books which specializes in LGBTQ+ literature.

Outside of professionally published work, an abundance of romance and erotica writing can be found online. Literotica is one of the OGs of erotic writing on the internet. That the website apparently hasn’t been redesigned since 1998 only adds to its charm.

If you want to try writing romance or erotica yourself, there are plenty of places to find a readership online. Reddit’s

r/eroticauthors community is full of writers and readers happy to share tips on the craft and provide feedback on your writing.

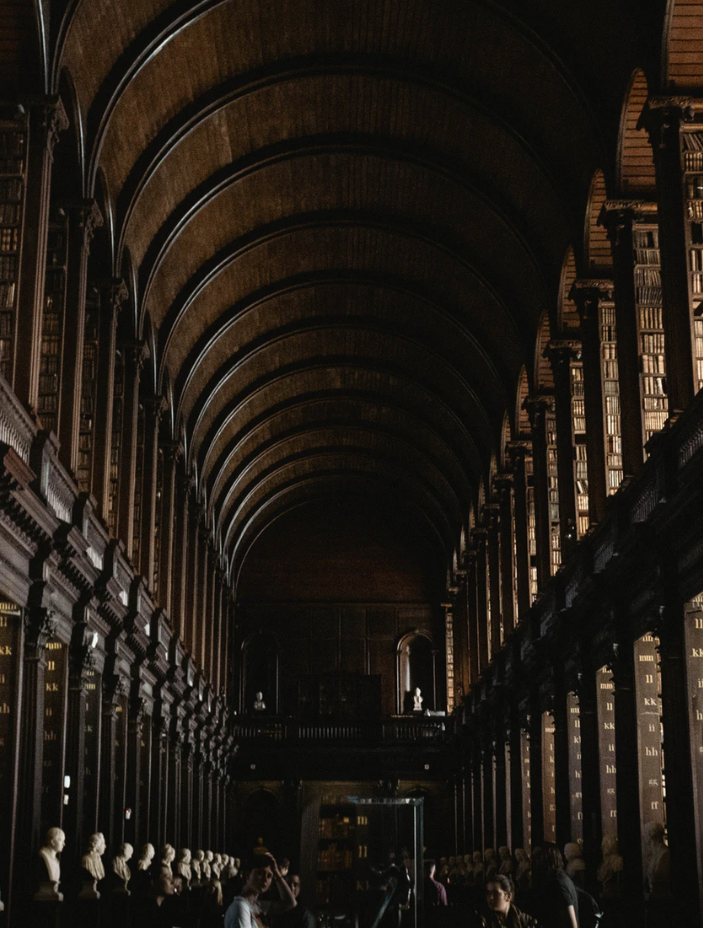

A Short History of Smut.

leaving everything on the page.

if you’ve watched bridgerton, picked up a title from the romance section at the bookstore, or attended a viewing of fifty shades, you’ve encountered your fair share of smut.

haven’t heard the term before? it’s fairly simple: smut refers to a work of fiction (typically written) that is sexual in nature. per urban dictionary, smut is most often, though not always, geared towards women (who are 84 percent of romance book readers, too).

smut is a kind of erotica: a type of literature or art made intending to arouse the reader or viewer, per dictionary.com. but there is some debate on the internet about what can be considered smut versus erotic romance—where is the line drawn? one writer lays it out: erotic romance typically involves sex, among involved plot lines and emotional arcs. smut may or may not have similarly developed storylines, but it also has one clear differentiator: it devotes much more time and description to sex scenes. in a smutty book, there are no “off stage” sex scenes.

not all romance stories are smut, and whether or not a writer or reader considers them so can ultimately come down to personal opinion. but at the end of the day, when whatever you’re reading doesn’t shy away from describing a sexual encounter—no detail spared—you can pretty safely consider it smut.

smut is pretty much as old as civilization, too—here’s a quick history of the art form made to turn you on.

smut in ancient times

written by a greek novelist in the second century a.d., daphnis and chloe is a love story—one that (shockingly, considering the trajectory of most ancient greek storylines) has a happy ending. daphnis and chloe are both abandoned at birth, and they grow up as childhood friends, living a bucolic life. they fall in love (of course) and are taught by a shepherd that there is “there is no remedy for love, that can be eaten or drunk, or uttered in song, save kissing and embracing, and lying side by side.”

smut in medieval times

what better way to cheer up after a plague than with some smut? that’s a thought the 14th-century italian author giovanni boccaccio had when he wrote the decameron, a short story collection of over 100 tales, told from the perspective of a group of young women and men quarantined outside of florence to avoid the black death. given the circumstances, it’s not too surprising that a number of the stories would contain more erotic descriptions (and some penis jokes, too).

smut in victorian times

victorian england was known for its strictness and purity culture. so, of course, it was the perfect crucible for many authors to write and publish smut—which would typically get banned. one such work is my secret life, a once-anonymous 11-volume epic detailing the author’s sexual development and escapades. it’s unclear how much of this 4,000-page work was fictionalized, so it’s possible it can’t truly be considered smut by that virtue—but historians may be beyond the point of fact-checking all the book’s lurid details. it did take over 100 years for them to uncover the author’s identity, after all. in 2000, the ian gibson biographer named henry spencer ashbee as the book’s writer.

smut today

it is not hard to find smut today, whether you log on to the fan fiction publishing platform, archive of our own (ao3), or drop by your local bookstore to pick up a court of thorns and roses or any other smutty recommendation that’s been circulating on tiktok. if there’s one thing humans are going to do, it creates vivid, steamy fantasies to help themselves and others get off. in the realm of human history, smut is a constant.

erotic-ish novels to read in public.

literotica that can be hidden in plain sight.

history's raunchiest love letters.

the greats that mastered the raunchy missive long before technological innovations.

A Brief History of Love Poetry.

your introduction to the earliest writings on sex.