A Brief History of The Diaphragm.

Looking back at the female condom.

The project of pregnancy prevention dates back to the stone ages—and in turn, its history is quite the colorful one. Back in the 17th and 18th centuries, men used things like animal bladders as condoms, and pastes made of crocodile dung for spermicide. At the start of the 20th century—before oral contraception was cleared by the FDA in the ‘50s—women were spraying Lysol and other antiseptics into their vaginas under the guise that it might quell fertility. But after the widespread dissemination of the condom—and before the emergence of The Pill—one other form of female birth control took up some prominent space on the scene: The Diaphragm.

While rarely circulated anymore—largely due to the fact that each diaphragm should be custom-fit at a doctor’s office and is often thus both expensive and cumbersome (both to manufacture and procure)—they still play an essential role in the broader history of contraception in the United States.

For some essential context, the standard diaphragm is a silicone dome inserted into the vagina during sex, which, like a condom, acts as a physical barrier between egg and sperm. That said, a diaphragm must be used with a spermicide (when used without spermicide, it’s only 80% effective—and even with spermicide, it’s only 88% effective). With nearly 100% effective options on the market like birth control pills, IUDs, and patches, it makes sense that doctors aren’t vending the diaphragm as an ideal form of contraception, anymore. On the flip side, however, the device does represent a hormone-free, non surgical birth control option for women—which is not easy to come by, these days.

Invented in 1841, the diaphragm is actually among the oldest medical contraceptive tools we have (though the thing was largely outlawed in the U.S. throughout the early 20th century—so it hasn’t always been accessible). While creative (often absurd) DIY cervical barriers were already popular (to name a few: lemon halves, algae, sponges, even balls of opium), German gynecologist Friedrich Wilde was the first to craft rubber pessaries with custom-made molds—a concept that made its way to the U.S. in the 1850s, thanks to Charles Goodyear (yes, the tire guy).

Immediately following its arrival, the diaphragm was a hit—women were delighted to have more agency over their own pregnancy prevention, and so were their doctors. But due to the 1870 Comstock Laws—a decree criminalizing the possession, advertisement, and mail-order dissemination of “obscenities” like birth control—they were quickly made illegal in the United States.

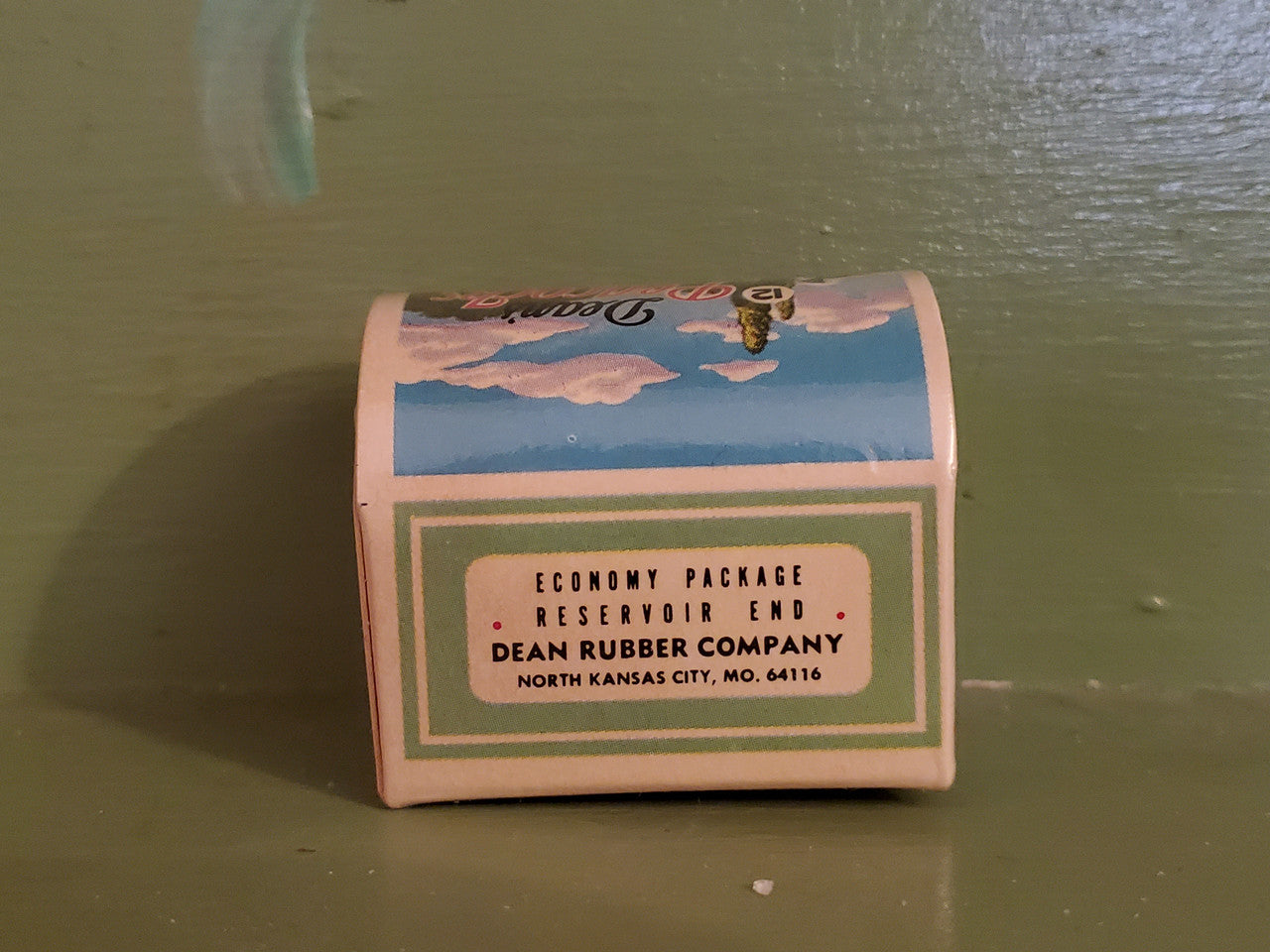

That’s where Margaret Sanger comes in: The radical feminist often credited as the mother of birth control as we know it. While traveling in holland, Sanger learned about Wilde’s diaphragms and so she brought the concept back to the U.S.—before she was arrested in 1916 for violating obscenity laws as the result. Fortunately—port-arrest—she had a back-up plan. She began importing diaphragms from Germany and Holland to her husband’s Montreal oil factory, where he loaded them into packing cartons and sent them, on his oil trucks, to New York—her way of circumnavigating the Comstock Law clause about distributing birth control via mail.

In the ‘20s, however, Sanger made another major stride: She helped to overturn the Comstock Laws by participating in a lawsuit over a package of diaphragms, shipping from Japan to a doctor in New York, that was confiscated. The judge ruled that the government had no business standing in the way of doctors providing effective contraception to their patients.

By 1941, doctors were freely recommending the diaphragm as the most effective, safest form of birth control for women—and while the tool lost its stature with the invention and dissemination of oral contraceptives and IUDs, it did mark a major step forward in a woman’s capacity to make choices about her own pregnancy prevention. And while now, the devices are not easy to find per se—the primary manufacturing company responsible for diaphragms ceased to produce them in 2013—you can still talk to your gynecologist about smaller-scale producers if you’re interested in an impermanent, hormone and surgery free mode of birth control.