Sex sells: the history of sex in advertising.

Does an ad for weedkiller really need nudity in it?

“Sex sells” is one of those universally-known truths that just seem so nakedly (ha) obvious that they are beyond question, but does it?

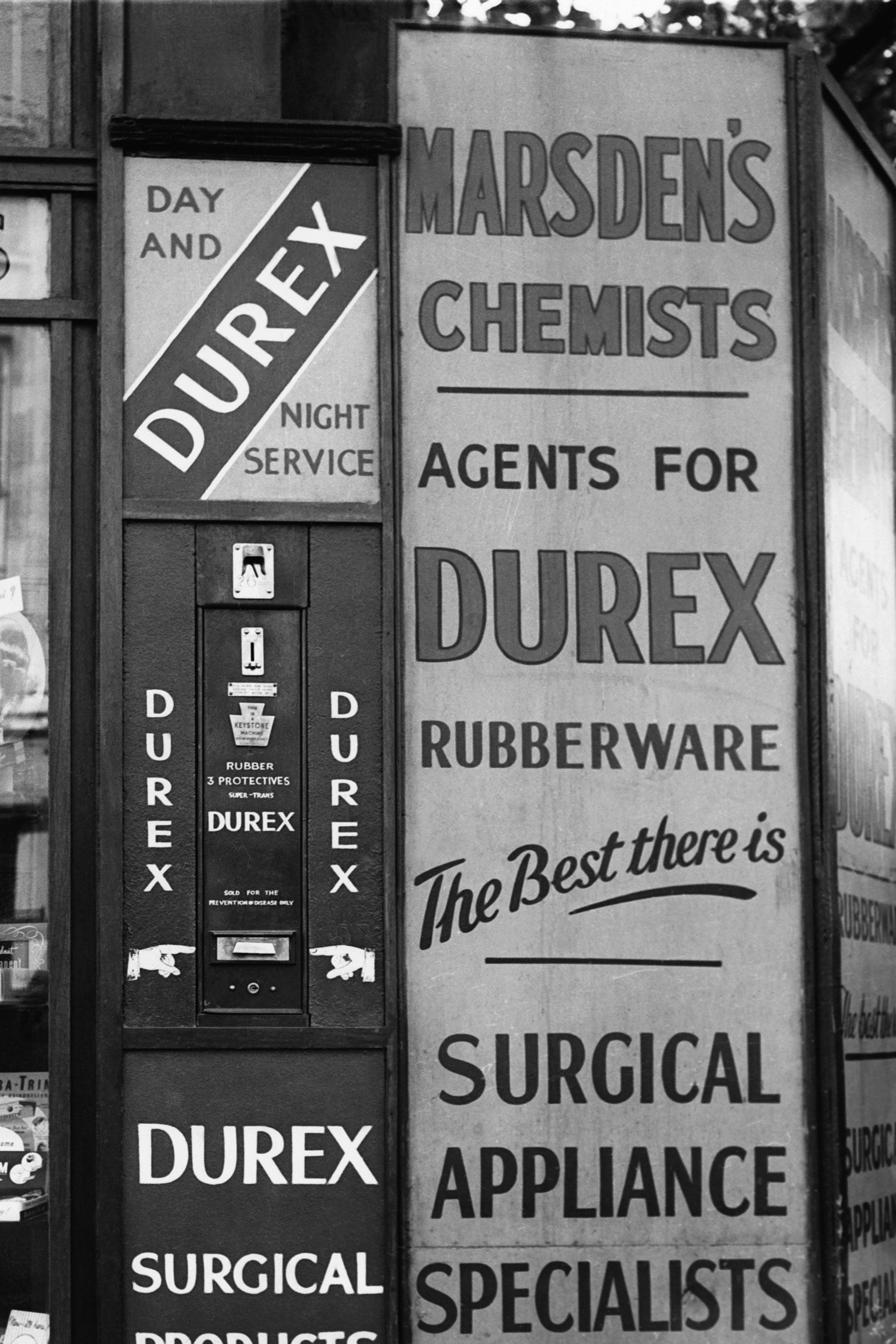

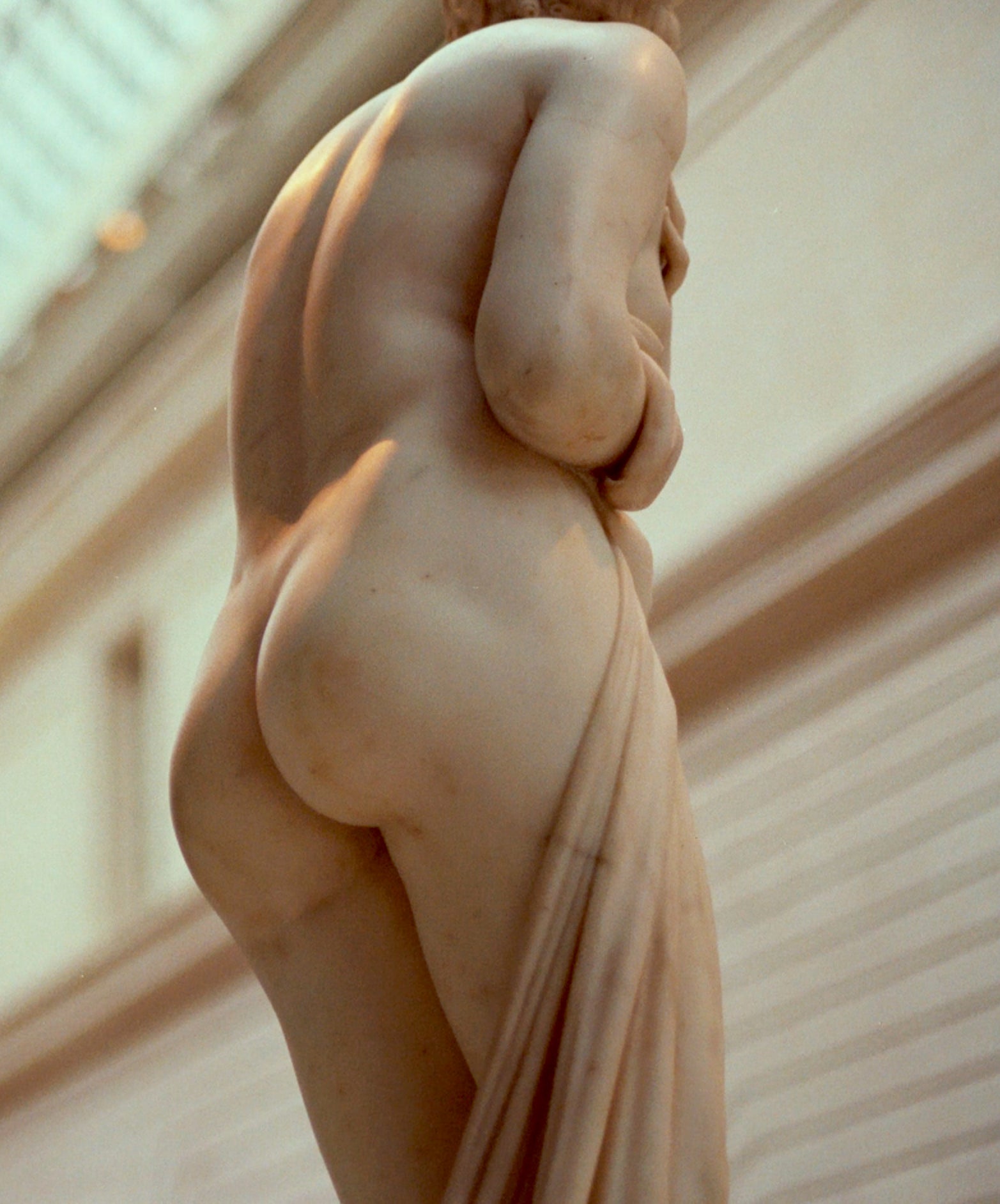

In 1871, the tobacco brand Pearl began using a painting of a naked Venus-like figure rising from the waves on its cigarette packets. Duke & Sons, another tobacco company, began inserting cards showing popular actresses of the day into their packets—they seem impossibly tame to modern eyes but worked, with Duke becoming America’s most popular cigarette brand.

Companies began pushing boundaries—again, in ways that seem fairly quaint to us—with Woodberry Soap featuring a completely nude female model (shot in a way that concealed her more controversial body parts) in 1926. Ads continued to get sexier and sexier, particularly in the fashion world, with the majority of advertisements that featured women in any way presenting them as sex objects. One study looking at advertising in the 1960s and 1980s found that while the number of ads featuring or alluding to sex didn’t necessarily go up, they did become a lot more overt, unambiguous, and visual. In 1994, a series of billboards for Wonderbra featuring Czech supermodel Eva Herzigová was blamed for an increase in traffic accidents in the UK, as drivers were distracted by the ads.

There is, of course, a difference between selling a product that has a natural association with sex and sexiness, and one where it makes minimal sense. Lingerie ads pushing the sexy side of their products as a primary selling point makes absolute sense. Greased-up half-naked models advertising a waste disposal unit, plunger, or chainsaw make less.

Some products exist in an in-between space where it just about makes sense—while the main selling point of soap is generally that it cleans the dirt off, if it’s being pushed based on how it makes your skin feel to the touch, there’s kind of a sex connection here. A lot of health and fitness products make the same indirect connection—imagine how much sexier your life will be when you feel healthier/fitter/cleaner. Dr. Tom Reichert, who has written extensively on sex in advertising, has called this approach the “Buy this, get this” formula. He describes it as, “If you buy our product: (1) You’ll be more sexually attractive, (2) have more or better sex, or (3) just feel sexier for your own sake.”

With some products, these are harder arguments to make than others. Cat food, hearing aids, toilet paper, and foot fungus cream have all been sold with overtly sexual ads, albeit sometimes in a slightly tongue-in-cheek manner.

Modern consumers generally like to think of themselves as savvier than in the past, more aware of the manipulative techniques used by advertisers. Everyone is aware of the logical leaps involved. Seeing an outrageously attractive person drinking a particular brand of soft drink in an ad, anyone knows rationally that drinking the same soft drink will neither render them as attractive as the person in the ad nor make the person in the ad want to have sex with them.

Gen-Z audiences are also arguably less likely to be so dazzled by the sexiness on offer that they turn a blind eye to dodgy business practices. Some of the fashion brands which spent the 1990s most aggressively marketing themselves as sexy have gone through very turbulent times and public reappraisals, with both Victoria’s Secret and Abercrombie & Fitch—sold respectively by lingerie-clad supermodels on catwalks and underwear-clad store assistants—the subjects of fairly damning investigative documentaries in 2022 alone.

Yet, it would be ridiculous to suggest that sex didn’t still sell. Around 40% of complaints to authorities about advertisements are sex-related. The mobile gaming market is fairly notorious for using cleavage-filled ads to sell apps completely unrelated to sex—top-down RPG games sold with hyper-sexualized ads, or simple color-matching games promoted with interactive ads that seem like they are promoting something else entirely.

Studies have shown that sex in advertising is more frequently used to sell impulse purchases—clothing, food, drinks, health and beauty items—rather than larger investments, but more expensive purchases like cars and vacations still often use traditionally attractive models with the inference that having/doing/buying these things might in some way equate you with these beautiful sex-havers.

Sex appeals to almost everyone, so it makes sense as a vehicle by which to make something else appeal—associating a product with that most fundamental of human desires. It doesn’t always work, though. Sex might be a powerful way of getting a message across, but that message might just be “hey, look, that’s sexy” rather than “hey, look, that’s sexy and I should purchase this other product”. A study in 2021 found that viewers of highly sexual ads tended to remember the sexual content they had seen, but not necessarily remember the brand being advertised. That’s a failure as far as advertising intent goes.

Sex will always be used to sell sexy things, but the days of flinging some attractive half-naked people into an ad for drain cleaner might be over.