A history of Hollywood and body hair.

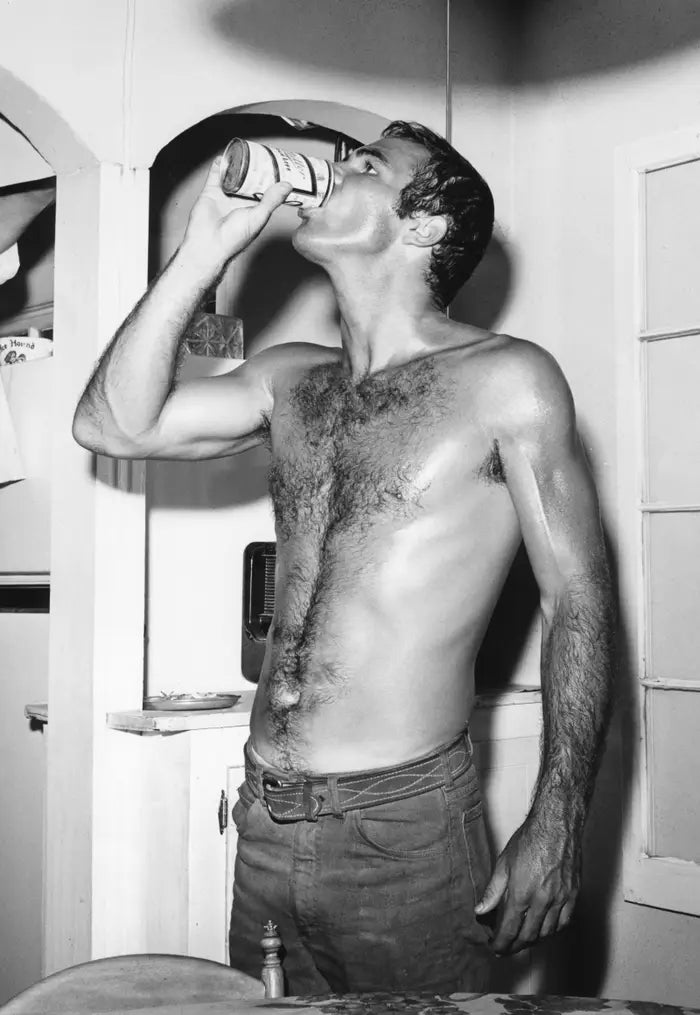

Body hair has been embraced, rejected, removed and recreated by Hollywood over the years.

Art in general has always had a complicated relationship with public hair — the upper pubic region could be pictured with no hair and be seen as perfectly tasteful, while a glimpse of pubic hair somehow made the whole thing obscene. Most Renaissance nudes don’t have Renaissance pubes.

Female ones, anyway — Vitruvian Man and other male nudes sport healthy bushes. The general rule of thumb in art, historically, seems to have been that on a nude depiction of a man, pubic hair does a bit of obscuring and makes things less obscene, while on a depiction of a woman, pubic hair draws attention to the genital area and makes it more so.

In the early days of Hollywood, as both emerging filmmaking technology and a nascent film industry found their feet, the general attitude was to go for it, but within a generally restrictive climate where there was no way of openly profiting from material deemed obscene. There are surviving early silent films featuring both real and simulated nudity (using bodystockings) — 1915’s Hypocrites features a nude ghost, portrayed by Margaret Edwards, whose pubic hair is clearly visible.

However, most nudity in early films was more suggestive than explicit, and generally limited to breasts and buttocks, with nary a pubic hair to be seen. This was still an environment in which exposed legs could cause something of a furore, and a navel on display was cause for a riot.

In the 1930s, the Hays Code — a supposedly voluntary system that in reality studios had to abide by if they wanted their films to be publicly shown in America — banned any “licentious or suggestive nudity”. One way filmmakers got around this was to create faux-educational films — leering quasi-documentaries or films about the consequences of drug abuse, which would feature fleeting glimpses of nudity.

However, pubic hair was still seen as largely beyond the pale — it was viewed as essentially an extension of genitals themselves, which there was no getting away with. When people were shown nude, carefully-angled legs would obscure key areas. 1954’s nudist movie Garden of Eden somehow features dozens of naked people without a pube to be seen.

The 1960s was a pretty dramatic decade for mainstream on-screen nudity — a single breast shown in 1960’s Peeping Tom drew huge controversy, but by 1970 something called ‘nudie cuties’, B-movies featuring as many topless women as could be crammed on screen, were commonplace.

Pubic hair remained largely off-limits in American films until European arthouse cinema shifted the boundaries. In 1966, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup featured a brief shot in which a woman’s pubic hair was undeniably the focus, one of several issues that resulted in it being denied a Production Code by the MPAA, something which was pretty much seen as the end of the Hays Code having any relevance. 1967 and 68 saw the Swedish movies I Am Curious (Yellow) and I Am Curious (Blue), both of which featured extensive full-frontal male and female nudity complete with pubic hair, go on general release to high acclaim. 1969’s Women In Love had pubes aplenty and won an Oscar.

Around this time, pubic hair became the focal point of an ongoing rivalry in newsstand publishing as Playboy and Penthouse magazines became embroiled in “the pubic wars”, trying to outdo one another in terms of what they showed without being shut down. This arguably had an effect on mainstream acceptance of nudity in all media, and by the 1970s movies could really go for it. The MPAA brought in the R and X ratings, legitimising on-screen nudity to some extent.

In the 1970s and 80s, pubic hair was everywhere. The New Hollywood movement, spearheaded by directors like Martin Scorcese and Francis Ford Coppola, aimed to tell gritty and realistic stories, which included sex and nudity. Andy Warhol’s Blue Movie led to ‘the Golden Age of Porn’, with adult movies shown in mainstream cinemas. Lowbrow sex comedies, exploitation films and B-movies gleefully embraced the ability to show full-frontal (almost exclusively female) nudity.

Pubic hair appeared in non-sexual contexts as well. John Waters is fascinated with it, artistic, almost abstract close-ups form part of the plot of his 1999 movie Pecker. Other instances include hairs slathered on a pizza in She’s All That, glued to a cast member’s face in Jackass Number Two and cut with a hedge trimmer in Scary Movie 2.

Trends change, including with pubic hair, and there’s less of it about than once there was, a trend generally seen as linked to the rise of internet porn in the late 1990s (along with thongs, low-rise jeans and smaller swimsuits). Due to this, a small cottage industry has appeared in Hollywood constructing merkins, or pubic wigs.

These provide two functions — making a performer who has removed their own pubic hair appear more historically accurate in anything set before about 1998, and providing a modicum of modesty, meaning they can be naked but not too naked. The last decade or so has seen a lot of nudity-filled TV shows set in the past (or in worlds that resemble the past), with Boardwalk Empire, Game of Thrones, Rome and Spartacus surely spending millions on prosthetic pubes.

But pubic hair is very much making a comeback, with more and more people opting to make grooming decisions based on personal comfort rather than trends. Pubic hair has been embraced, rejected, removed and recreated by Hollywood over the years, used for titillation, drama and comedy.

Life imitates art, art imitates life, and life contains pubes.